An opinionated guide to Classical Chinese Philosophy

An introduction to the three main schools in classical Chinese philosophy, and spelling out the parts that don’t make sense.

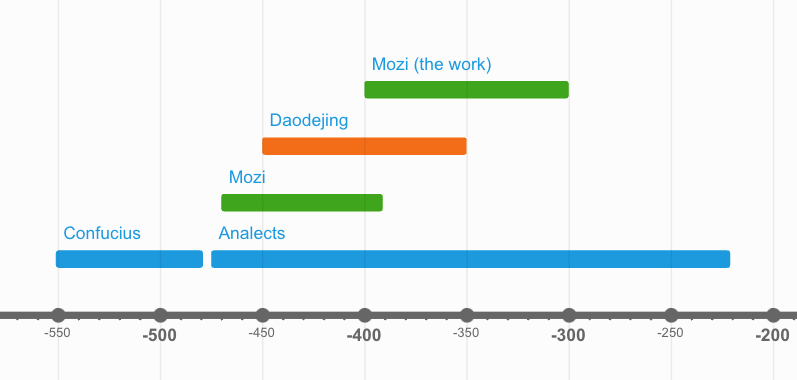

Rough timeline

We’ll focus on three foundational texts: the Analects, the Daodejing, and the Mozi. These works represent the core ideas of Confucianism, Daoism, and Mohism, respectively.

The Analects is a collection of sayings attributed to Confucius, compiled by his followers. The Mozi, likewise, is a compilation of the teachings of Mozi and his followers. The Daodejing, traditionally attributed to Laozi, is believed to have been written by multiple authors. Some even question whether Laozi ever existed.

But what’s important here is the Analects came first. The Daodejing and Mozi, compiled later, were influenced by and react to the Analects.

Confucianism

End goal

Confucianism’s ultimate goal is restoring the way (道, Dao) of harmony (和, He).

The gentleman cultivates the roots. When the roots are established, the Dao will grow. (Analects 1.2)

But what’s the difference between “the way of harmony” and “harmony”? There’s no clear distinction in the text. So, to keep things straightforward, the end goal of Confucianism is to restore harmony.

Harmony (和, He)

What is harmony? It is both an abstract philosophical concept and a practical virtue1.

Harmony as a philosophical concept

Philosophic harmony has a few key characteristics: 2

- Harmony involves heterogeneous parts

Rather than forced conformity, Confucian harmony entails diverse elements working together. Confucian harmony values balance and respect for differences, where these differences complement and support one another.

The gentleman harmonizes, and does not merely agree. The petty person agrees, but he does not harmonize. (Analects 13.23)

- Harmony creates something larger than a sum of its parts

Confucian harmony is about creating something greater than individual contributions. The scholar-minister Yan Ying, a contemporary of Confucius, illustrates this via the process of making soup:

He is like making soup. One needs water, fire, vinegar, sauce, salt, and plum to cook fish and meat. One needs to cook them with firewood. The cook needs to mingle (he) ingredients together in order to balance the taste. He needs to compensate for deficiencies and to reduce excessiveness. In eating [such balanced food], the virtuous person (junzi) achieves a balanced heart-mind. (Thirteen Classics with Commentaries)3

Taken together, harmony is a process where heterogeneous parts actively work together to create something larger than the sum of its parts.

Harmony as a practical virtue

The Analects extends the concept of harmony to the individual4. Confucius stressed that to achieve personal harmony, you have to balance your internal flow of vital energy (气, Qi),

A virtuous person exercises three cautions. In youth, his physical vitality (xue-qi 血氣) has not yet settled, so he needs to guard against lust. When he reaches his prime, his physical vitality is full of vigor, so he needs to guard against contention. In old age, his physical vitality is declining, so he needs to guard against being covetous. (Analects 16.7)

and also balance the virtues to avoid extremes or flaws in character.

The latent flaw in being fond of human-heartedness without being fond of learning is that it leads to foolishness. The latent flaw in being fond of wisdom without being fond of learning is that it leads to dissipation. The latent flaw in being fond of trustworthiness without being fond of learning is that it leads to harm’s way. The latent flaw in being fond of uprightness without being fond of learning is that it leads to bluntness. The latent flaw of being fond of courage without being fond of learning is that it leads to disruptiveness. The latent flaw of being fond of steadfastness without being fond of learning is that it leads to recklessness (Analects 17.8)

The five virtues of a Junzi

To achieve personal harmony, Confucius teaches that people should cultivate the virtues of a gentleman (君子, Junzi).

1. Benevolence (仁, Ren)

Ren refers to considering the needs of others, particularly in the private sphere. It is a broad virtue that encompasses humaneness, kindness, and compassion.

If a person sets his heart and mind firmly on ren, he will be free of malevolence (Analects 4.4)

It is also related to the silver rule5.

What you don’t want done to yourself, don’t do to others (Analects 12.2)

2. Appropriateness/Righteousness (义, Yi)

Yi is the virtue of moral judgment, shaped by the action, its context, and the recipient.

The junzi is not dogmatic in his ways. He simply follows what is yi. (Analects 4.10)

In the realm of public responsibility, Yi values steadfastness and appropriateness in the face of temptation.

The junzi understands what is right. The petty person understands what is beneficial. (Analects 14.42)

However, familial relationships are the most important of all, overriding even official rules or public expectations.

“When his father stole a sheep, he reported him to the authorities. Kongzi replied, ‘Among my people, those who we consider “upright” are different from this: fathers cover up for their sons, and sons cover up for their fathers. “Uprightness” is to be found in this.’” (Analects 13.18)

3. Propriety and rituals (礼, Li)

Li involves fulfilling one’s responsibilities and maintaining proper conduct in social hierarchies.

A lord should employ his ministers with ritual, and ministers should serve their lord with dutifulness (Analects 3.19)

One manifestation of Li is filial piety — children should respect and provide for their parents unconditionally.

Ziyou asked about filial piety. The Master said, “Nowadays ‘filial’ means simply being able to provide one’s parents with nourishment. But even dogs and horses are provided with nourishment. If you are not respectful, wherein lies the difference?” (Analects 12.4)

A child is completely dependent upon the care of his parents for the first three years of his life—this is why the three-year mourning period is the common practice throughout the world. (Analects 17.22)

Also, Confucius thought that rituals should be performed with sincerity and respect, rather than by rote.

When it comes to ritual, it is better to be spare than extravagant. When it comes to mourning, it is better to be excessively sorrowful than fastidious (Analects 3.4)

If I am not fully present at the sacrifice, it is as if I did not sacrifice at all. (Analects 3.12)

Finally, rituals done sincerely reinforce the other virtues.

If you try to guide the common people with coercive regulations and keep them in line with punishments, the common people will become evasive and will have no sense of shame. If, however, you guide them with Virtue, and keep them in line by means of ritual, the people will have a sense of shame and will rectify themselves. (Analects 2.3)

4. Wisdom (智, Zhi)

Wisdom allows one to discern right from wrong.

Fan Chi asked about Goodness. The Master replied, “Care for others.” He then asked about wisdom. The Master replied, “Know others.” (Analects 12.22)

I asked the Master about wisdom, and he replied, ‘Raise up the straight and apply them to the crooked, and the crooked will be made straight.’ (Analects 12.23)

5. Trustworthiness (信, Xin)

Trustworthiness enables a Junzi to be given responsibilities, and a leader to rule effectively.

Zigong said, “If sacrificing one of the two remaining things [food and the trust of the people] became unavoidable, which would you sacrifice next? The Master replied, “I would sacrifice the food. Death has always been with us, but a state cannot stand once it has lost the confidence of the people.” (Analects 12.7)

Generous, he won over the masses. Trustworthy, the people put their faith in him. Diligent, he was successful. Just, [the people] were pleased. (Analects 20.1)

Other concepts

Beyond the five virtues, Confucius also highlighted other ideas for achieving harmony.

Rule by virtue

A ruler should rule by virtue, not by law or punishments.

When the ruler is correct, his will is put into effect without the need for official orders. When the ruler’s person is not correct, he will not be obeyed no matter how many orders he issues (Analects 13.6)

The Rectification of Names (正名, Zheng Ming)

If a ruler calls himself a “leader” but acts selfishly and neglects his people, his title no longer fits reality, causing confusion and distrust. In contrast, when a “leader” genuinely fulfills his duties — protecting and providing for his subjects — his name aligns with his role, setting an example that resonates through society.

The general principle is that when names align with their true meaning, social roles and actions follow naturally. Hence, words and names must accurately reflect reality.

If names are not rectified, speech will not accord [with reality]; when speech does not accord [with reality], things will not be successfully accomplished. When things are not successfully accomplished, ritual practice and music will fail to flourish; when ritual and music fail to flourish, punishments and penalties will miss the mark. And when punishments and penalties miss the mark, the common people will be at a loss as to what to do with themselves. (Analects 13.3)

An agent of order

You can see the vision Confucius paints of an ideal person and society — hierarchical, orderly, and proper. His philosophy has deeply shaped Eastern thought and culture, practiced in varying degrees by ~1.5 billion people of East Asian heritage worldwide. Today, you can see Confucian values reflected in Guanxi, guess culture, and good ol’ filial piety. Whether you embrace or reject Confucian ideas, their historical and cultural impact is undeniable.

Daoism

Now, the the problem with Daoism is that it doesn’t even bother to define itself properly, for…

The Dao that can be named is not a constant Dao

The Dao that can be followed is not a constant Dao.

A name that can be named is not a constant name

(Daodejing, Chapter 1)

We can take this to mean

- Nihlism: The is no true Dao

- Skepticism: The Dao is fundamentally unknowable

- Anti-language: Language cannot fully capture the Dao

Either way, not a great start6. The Daodejing also describes the Dao as the genesis of all things,

The Dao produces the One. The One produces two. Two produces three. Three produces the myriad creatures. The myriad creatures shoulder yin and embrace yang, and by blending these qi, “vital energies,” they attain harmony.(Daodejing, Chapter 42)

The Dao is like an empty vessel; No use could ever fill it up. Vast and deep! It seems to be the ancestor of the myriad creatures.

(Daodejing, Chapter 4)

a way to live,

To be a true king is to be Heavenly. To be Heavenly is to embody the Dao. To embody the Dao is to be long lived, And one will avoid danger to the end of one’s days. (Daodejing, Chapter 16)

obscure, vague, and elusive,

The outward appearance of great Virtue comes forth from the Dao alone. As for the Dao, it is vague and elusive. …It is how we know the origin of all things. How do I know what the origin of all things is like? Through this! (Daodejing, Chapter 21)

and contradictory.

The clearest Dao seems obscure; The Dao ahead seems to lead backward; The most level Dao seems uneven; (Daodejing, Chapter 41)

Confused? Yeah, me too. Even if we could piece together an internally consistent definition of the Dao, would it be valid anyways, for the Dao that can be named is not the constant Dao?

The SEP regards Daoism as “one of the two great religious/philosophical systems of China”, alongside Confucianism. I wonder how is a book whose central thesis is so vaguely defined — or undefinable — be influential in ancient Chinese thought?

Wu wei (non-action)

The Daodejing urges us to act without acting — this is called wu wei. Wu wei is often misunderstood as doing nothing at all, but it’s closer to acting effortlessly and without force. Think of it like Laissez-faire capitalism — minimal intervention produces maximal results.

“The Dao never acts, yet nothing is left undone.” (Daodejing, Chapter 37)

Wu wei is like water flowing around rocks. The best actions are the ones that flow naturally rather than those that forcefully push against the world.

Those good at fighting are never warlike. Those good at attack are never enraged. Those good at conquering their enemies never confront them. Those good at using others put themselves in a lower position (Daodejing, Chapter 68)

The problem with Wu wei is that it doesn’t specify when we should use less intervention, other than “when it makes sense” (which is the equivalent of saying nothing at all). This means Wu wei suffers from the same problem as other concepts from the self-help genre — its good advice for some and bad for others. Imagine someone destroying their life with crack and the advice you offer them is to “do nothing yet leave nothing undone”?

Ziran (Naturalness or Spontaneity)

Ziran means “naturalness” or “spontaneity.” Daoism holds that everything in the world has its way of being, and things reach their fullest potential when they follow that natural way without outside interference.

“Man takes his law from the Earth; the Earth takes its law from Heaven; Heaven takes its law from the Dao; the Dao takes its law from what is naturally so.” (Daodejing, Chapter 25)

This clashes with Confucianism, which stresses rigid rules and social expectations. Daoists believe we should let go of these.

“Cut off ren and abandon yi, and the people will return to being filial and kind. Get rid of cleverness and abandon li, and thieves and gangsters will not exist” (Daodejing, Chapter 19)

Confucian virtues like kindness (ren) and righteousness (yi) can disrupt our natural state.

When the great Dao is abandoned, there are benevolence and righteousness. When wisdom and intelligence come forth, there is great hypocrisy (Daodejing, Chapter 18)

Wisdom and cleverness often lead to hypocrisy, not peace.

Get rid of learning and there will be no anxiety! (Daodejing Chapter 20)

So, Daoism suggests we should focus less on trying to be virtuous in a structured way and instead embrace the simplicity of just being ourselves, in tune with the Dao.

Taken charitably and uncharitably

Taken charitably, Daoism is a philosophy that encourages spontaneity and authenticty. It urges us not to take social norms too seriously, and to go with the flow.

However, a critical reading of the Daodejing makes it hard to be charitable. It’s easy to feel like the Daoist criticisms of wisdom, ren, and yi are just the authors being petty towards Confucianism. There’s no real substance to some of these jabs, just a quick dismissal of things they didn’t like.

There is also a lot of wuwei-esque, r/iam14andthisisdeep contrarianism:

The great square has no corners; The great vessel takes long to perfect; The great note sounds faint; The great image is without shape (Daodejing, Chapter 41)

To top it off, Daoist interpreters disagree with each other irreconcilably about the foundational ideas of the Daodejing.

Nearly every ‘fact’ associated with Lao Tzu or the Tao Te Ching is countered by alternative theories and arguments too complex to unravel in anything short of a full-length work on the history of Tao Te Ching scholarship…different translations of the same lines sometimes differ even in their fundamental propositions… (On Translating the Dark Enigma: The Tao Te Ching)7

After thousands of years of scholarship, if we still aren’t anywhere close to a universally accepted list of the key ideas, then maybe Daoism not as profound as it’s made out to be.

Mohism

End goals

The Moists were state consequentialists. Originally experts in defensive warfare, their philosophy is primarily concerned with achieving security and prosperity for the state. They defined utility as the wealth, order and population size. Anything that contributed to these goals was considered good.

“Does it benefit people? Then do it. Does it not benefit people? Then stop” (Mozi, Chapter 32)

The Ten Doctrines

The Mozi outlined ten main doctrines, which guided their ethical and political views:

- “Promoting the Worthy” and “Identifying Upward”

- “Universal love” and “Condemning Aggression”

- “Moderation in Use” and “Moderation in Burial”

- “Heaven’s Intent” and “Understanding Ghosts”

- “Condemning Music” and “Condemning Fatalism”

The first meritocrats

The Moists were the earliest advocates of meritocracy in China. Promoting the Worthy meant that leaders should be chosen for their abilities, not their family background—a radical idea at the time.

The wise should be promoted and the able should be employed. It is the way of the sage-kings to select the worthy and talented and to assign them responsibilities. (Mozi, Chapter 8)

Mozi recommends that we implement meritocracy via a system of rewards and punishments. We can contrast this with Confucius — Confucius would approve or disapprove, while Mozi would reward or punish.

If those who are good are not rewarded and those who are bad are not punished, and government is conducted like this, the state and its populace will certainly be in disorder. Therefore, a failure of rewards and punishments to accord with the feelings (conditions) of those below is a matter which must be examined. (Mozi, Chapter 13)

Identifying Upward meant that people of lower ranks should take their standards from those above them. So, bureaucrats should look to the king’s example, and the king should get his standards from Heaven (天, Tian). However, what exactly Tian’s standard meant was left vague in Mozi’s writings, leaving its application unclear.

“In government, those below take the lead from those above, and those above take Heaven as their model.” (Mozi, Chapter 15)

Achieve rigour with objective standards and argumentation

A carpenter uses a steel square to measure angles accurately. Likewise, Mozi argued that societies need objective standards to guide decision-making. This emphasis on objectivity can be interpreted as a response to Confucian ideas about following family example—Mozi believed that not all parents or ancestors set good examples.

One who governs must measure by what is beneficial to the world, taking this as his compass and square. If something is beneficial to the world, then do it; if it is harmful, stop. (Mozi, Chapter 32)

Mozi also promoted the idea of argumentation (辩, Bian), encouraging people to evaluate claims based on evidence, precedent, and practical outcomes rather than tradition.

When disputes arise, they should be settled based on precedent, by drawing comparisons, and by examining how things are done in practice. If we consider and weigh each of these aspects, we can arrive at the correct answer. (Mozi, Chapter 39)

Mozi critiqued Confucian values that prioritized tradition or familial loyalty without objective grounding. He argued that simply following one’s parents or customs without questioning the consequences could lead to misguided or unjust actions.

Universal love (兼爱, Jian Ai)

Mozi’s concept of universal love argues that social problems arise from excessive partiality. He believed that if people treated others with the same love and respect they give to their own family or state, society would become more peaceful and harmonious.

“If people regarded others’ states in the same way as they regard their own, then who would raise their states to attack the state of another? … If people regarded others’ families in the same way as they regard their own, then who would raise their families to cause disorder in others’ families?” (Mozi, Chapter 16)

This idea clashes with Confucianism’s view on family loyalty, which prioritizes special relationships over impartiality. For Confucians, love should be based on roles and responsibilities within a family or community, not extended universally.

Also, Mozi’s philosophy of universal love went hand-in-hand with his stance against offensive warfare. The Mohists argued that offensive war brought nothing but destruction and suffering, and was often driven by selfish motives rather than genuine need. Defensive warfare, however, was seen as a necessary measure to protect the state.

Moderation over extravagance

Mozi also called for Moderation in Use and Moderation in Burial, criticizing the excesses of the ruling class. At a time when most people were poor, rituals like extravagant burials and music were viewed as distractions that didn’t contribute to societal utility.

This was also why Mozi disliked music — the resources used to train and feed musicians and make musical instruments could be better used to improve the livelihoods of the people or defenses of the state.

Condemning Fatalism

Mozi opposed the idea that fate or cosmic forces control human outcomes. He argued that fatalistic beliefs led people to passively accept suffering and inequality, discouraging effort and responsibility.

“People who say things are destined by fate are lazy and unworthy. They fail to work hard and take no responsibility for their lives or their society.” (Mozi, Chapter 35)

Ghosts and heaven as a motivation for virtue

Understanding Ghosts and Heaven’s Intent suggested that virtue was necessary because Tian and ghosts would punish the wicked and reward the virtuous. Mozi believed that belief in this system could maintain order and stability in society.

“If the ability of ghosts and spirits to reward the worthy and punish the wicked could be firmly established as fact throughout the empire and among the common people, it would surely bring order to the state and great benefit to the people.” (Mozi, Chapter 43)

Interpreted charitably, ghosts and Tian could serve as a noble lie to encourage goodness, even when no one was watching.

A forgotten philosophy

Mohism is probably the philosophy that resonates most clearly with you, dear reader. Its focus on universal love, meritocracy, and rational governance offers a practical, almost modern approach to ethics and statecraft. While some aspects—like beliefs in ghosts and Tian—might seem out of step with contemporary thinking, the core message is clear.

Yet, Mohism has never had the long-lasting influence of Daoism or Confucianism. It’s a mystery why its vision of a more impartial and utilitarian society didn’t take root in Chinese culture. Perhaps the answer lies in how we value tradition and emotion in our moral systems — something Mohism, for all its strengths, didn’t fully account for.

-

This distinction is taken from Chapter 1 of The Virtue of Harmony ↩︎

-

In drafting this post, I originally stressed that Confucian harmony is the process, rather than the end state. Chenyang Li explains why in The Virtue of Harmony:

The primary Chinese character for harmony is “he 和” … In ancient texts, the word was primarily used as a verb—as in, “to harmonize”—rather than describing an accomplished state.

[Confucian] harmony can then best be characterized as dynamic harmony or active harmony… This type of harmony stands in contrast with passive harmony, in which there is peace and even coordination without active engagement. Passive harmony can be found in chapter 80 of the Daodejing, where the Daoist philosopher Laozi describes and prescribes an ideal harmonious society where people enjoy a primitive way of life. Internally, there is minimum effort for social construction toward progress. People live their lives in a natural way. It is passive insofar as it is not aimed to create something new but rather to resonate naturally with what already is. Confucians, however, consider this too much of a laissezfaire approach toward harmony.

Still, I struggled with the idea of a process being the ultimate goal of Confucianism. Taken to its logical extreme, an AI programmed to maximize Confucian harmony might repeatedly create disorderly societies, guide them through a process of harmonization, and then restart the cycle endlessly. This felt fundamentally wrong to me. ↩︎

-

Thirteen Classics with Commentaries《十三經注疏》1985, Zhongguo Shuju ↩︎

-

The Virtue of Harmony also makes the case for harmony as cosmic and social virtues. However, these are only fleshed out in later texts of the Confucian canon, so I chose to omit them. ↩︎

-

Silver rule: do not treat others the way you would not like them to treat you. ↩︎

-

This may be a form of apothatic theology. ↩︎

-

https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/epub/10.3366/tal.2022.0494 ↩︎