Transcendental Idealism, as clearly as possible

Immanuel Kant is one of the most influential, and unreadable, philosophers in the Western tradition. This post offers a gentle introduction to his central idea, Transcendental Idealism, aimed at intelligent lay readers who want clarity without sacrificing philosophical depth.

Transcendental Idealism, briefly

There is the world we experience (the phenomenal world) and the world as it exists independently of us (the noumenal world). Transcendental1 idealism is a claim about what is the relation between the two worlds.

Imagine looking at a chair: how it looks to you (its color, shape, position) is the phenomenal chair. But there’s also the chair as it actually is, independent of your perception—the noumenal chair. Transcendental idealism claims:

- Your mind structures how the chair appears to you — your experience of the world is mind-shaped

- We can never know what the chair in-itself is actually like — the noumenal is unknowable

What does it mean that the mind shapes our experiences? For Kant, space and time are not properties of the world, but properties of the mind. When you see a chair spread out in space, your mind takes raw sensory input from your eyes and organizes it spatially so it’s not just a blob of color. When you hear someone speak, your mind arranges the syllables in time to make them understandable. Space and time, then, are mental frameworks that let you experience the world.

Space and time help you see someone kick the chair. But to make sense of it, you also grasp that the foot caused the chair to move (causation) and that the chair stays the same chair even if a leg breaks off (substance). Without causation, the world would be a jumble of disconnected events. Without substance, you couldn’t tell if anything persists through change. Kant says the mind has 12 built-in concepts—causation and substance among them—that organize experiences into a coherent whole. Later, we’ll explore others like oneness, manyness, or negation.

Yet Kant also insists the chair exists in the noumenal world, beyond our perception. Without something “out there,” you wouldn’t experience a chair at all. This makes Kant an empirical realist2 — things are real within our experience.

Think of the mind as a projector with a lens. Without it, we’d see nothing. We know there’s a raw “video file” out there causing what we see, but the projection—filtered and shaped by the mind—is our only access. We can’t peek at the file itself; without the projector, it wouldn’t even make sense to us.

So, in simple terms, Kant’s system is this:

- We can only know the phenomenal world, not the noumenal world (though we know it exists as a cause).

- The phenomenal world is made up of perceptions triggered by things-in-themselves, but structured by our minds

- Things really exist in the noumenal world

Why do we care?

In Kant’s time, the 1700s, philosophers were wrestling with big questions about what humans can know. Are the laws of science, like Newton’s ideas about gravity, true a priori like 1+1=2? Can we answer deep questions like “Does God exist?”, “Do all events have a cause?”, or even “Do I exist?” These debates split into two main camps: empiricism and rationalism. Kant saw flaws in both approaches and developed transcendental idealism in response. Understanding his reasons will help us ground our knowledge of the world, and understand it’s limits.

The Empiricists: Knowledge Comes from Experience

Empiricists, like David Hume, said all knowledge comes from what we see, hear, or touch—our experiences. For Hume, even something as basic as cause-and-effect isn’t a fact about the world; it’s just us noticing that things happen together often.

Imagine you push a chair, and it moves. You do this again and again, and soon you think, “Pushing causes moving.” But Hume said all you’ve really observed is one thing (pushing) happening before another (moving). Your mind connects them because they happen together often, not because there’s a deep cause “out there”. For Hume, causation is merely constant conjunction of a cause and effect, with the mental expectation that the effect always follows the cause.

But Hume went even further. He said science relies on induction—assuming the future will be like the past. Hume demonstrated that this assumption isn’t merely unjustified, but is necessarily unjustifiable:

- Premise 1: To justify induction, we’d need to prove the future will always follow the past, either a priori or a posteriori.

- Premise 2: Can we justify it a priori (by pure thinking, without experience)? No, because we can imagine a world where the sun doesn’t rise tomorrow. It’s not a logical contradiction like saying “some bachelor is married” (Principle of Contradiction)

- Premise 3: Can we justify it a posteriori (through experience)? No, because all our experiences are from the past. We’ve seen the sun rise before, but that doesn’t prove it must rise tomorrow. Using past experiences to justify induction just assumes induction works, which is circular.

- Conclusion: So, induction can’t be justified either way—it’s a habit, not a truth.

Hume’s revelations were profound. He showed that scientific laws like “a body at rest remains at rest” had the same epistemological weight as “all ravens are black”. Both come from observation, and both could be overturned — one day, a ball might not stay put, just like we might spot a white raven. Hume’s point was that we can’t prove scientific laws are built into the universe’s fabric. They’re just patterns we’ve seen so far, and tomorrow could prove them wrong.

If we couldn’t achieve certainty about the natural sciences and causation, what about bigger questions like God or the soul? Hume was……pessimistic, to say the least.

If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning, concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion. (An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, David Hume) 3

Kant disagreed. He thought science and causation had to have some kind of a priori foundation, rather than be habits of thought. If Hume was right, we’d be stuck doubting everything, with no firm ground for knowledge.

The Rationalists: Knowledge Comes from Reason

On the other side were rationalists, like René Descartes and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who believed we could know truths about the world through pure thinking. Descartes started with one unshakable idea:

- Premise 1: I am thinking right now.

- Premise 2: If I’m thinking, I must exist to do the thinking.

- Conclusion: I exist

From this, Descartes argued we could logically figure out truths about ourselves, God, and the physical world, like building a house from a single strong brick. For example, he argued for God’s existence like this:

- Premise 1: I exist (established by “I think, therefore I am”).

- Premise 2: I have an idea of a perfect, infinite being (God).

- Premise 3: Every idea must have a cause with at least as much reality as the idea itself.

- Premise 4: I am imperfect (I doubt, I lack knowledge, etc.), so I cannot be the cause of the idea of a perfect being.

- Premise 5: Therefore, the idea of a perfect being must be caused by something that actually possesses that perfection.

- Conclusion: A perfect being—God—must exist to cause my idea of Him.

Leibniz took a different tack, saying our minds have innate ideas — built-in concepts we can analyze to uncover truths:

- Premise 1: The mind has ideas like “cause” or “substance” that don’t come from experience.

- Premise 2: By analyzing these ideas logically, we can learn about the world.

- Conclusion: Reason alone can reveal truths about reality, like how the universe works.

Kant thought the rationalists were also wrong. First, to even say “I am thinking,” you need to distinguish yourself from the world — me versus not-me. That means you’re already assuming things exist in space and time outside you, which undercuts Descartes’ starting point.

Second, Kant noticed rationalism led to dead ends. Using pure reason, philosophers could reach opposite conclusions about the same thing. For example, Kant gives an argument against the existence of a necessary, non-contingent being (God):

- Premise 1: A necessary being would either exist within or outside the world.

- Premise 2: If it exists within the world, it would be subject to the same conditions of time and causality as everything else, making it contingent (on the laws of the universe).

- Premise 3: If it exists outside the world, it cannot be known or verified through experience.

- Conclusion: There is no necessary, uncontingent being.

Kant called these opposite conclusions antinomies — contradictions that show reason alone can’t settle big questions about reality. The rationalists thought they could know the noumenal world (reality as it is, beyond experience), but Kant said they were overreaching. Our minds can only tell us about our experiences, not ultimate truths like God, the soul, or the universe’s start.

Metaphysics as a failed field

Kant saw metaphysics—the quest to understand reality’s deepest truths—in a total mess. Empiricists like Hume threw up their hands, saying we can’t know if tomorrow’s sunrise or gravity will work like yesterday’s. Rationalists like Descartes and Leibniz tried to answer everything with reason but ended up with contradictions.

Kant sought a middle path that would preserve the strengths of both approaches while avoiding their pitfalls. He believed:

- We can have certain, a priori knowledge about the world we experience, like science and causation.

- But we can never know anything beyond experience, like souls or the beginning of the universe

To get there, Kant took a first step: a finer-grained classification of propositions. Before him, philosophers distinguished knowledge epistemologically—based on how it’s justified.

- A priori knowledge is justified by rational intuition, independently of experience

- A posteriori knowledge is justified by experience 4

But Kant argued this wasn’t enough. He identified another axis to distinguish propositions: whether they are true by their meaning alone, or add something new beyond their meaning. This new distinction, missed by previous philosophers, would prove crucial.

The synthetic a priori

The analytic-synthetic distinction

A proposition’s meaning decides if it’s analytic or synthetic:

- Analytic proposition: The truth is contained in the subject’s definition. If you deny it, you get a logical contradiction—something that can’t make sense.

- Synthetic proposition: The truth isn’t contained in the subject alone. It adds something new, and denying it doesn’t lead to a contradiction.

In other words, there are two principles that govern analycity and syntheticity:

- Containment: an analytic proposition is entirely contained within the definition of the subject, while a synthetic proposition is not

- Contradiction: the negation of an analytic claim is a logical contradiction, while the negation of a synthetic claim is not

I find the best way to illustrate Kant’s analytic-synthetic distinction is to work thru some examples

- All bachelors are unmarried

- A priori, as it is justified by rational thought alone

- Analytic, as “unmarried” is contained within the definition of “bachelor”

- All bachelors are unhappy

- A posteriori, as it is justified by experience

- Synthetic, as “unhappy” is not contained within the definition of “bachelor”

- 7+5=12

- A priori, as it is justified by rational thought alone

- Synthetic. For Kant, ‘7+5=12’ isn’t just true by definition — you need to imagine adding quantities, step by step, which relies on your sense of time. The concept of “12” isn’t contained in “7 + 5.” For Kant, if you said “7 + 5 = 13,” it’s wrong but not a logical contradiction like “a bachelor is married.” 5

- A straight line is the shortest distance between two points

- A priori, as it is justified by rational thought alone

- Synthetic, as the concept of a straight line is not contained within the concept of the shortest distance between two points. You need a sense of space to infer that the shortest distance between two points is indeed a straight line. 6

- Every event has a cause

- A priori. You cannot prove that every event has a cause by experience, as you cannot experience everything. It must be justified a priori.

- Synthetic: The idea of “cause” isn’t built into “event.” To say an event must have a cause adds something new to “event”. Also, you can imagine an event without a cause.

- A body remains at rest or in uniform motion unless acted upon by an external force

- Synthetic, as the idea of being at rest or uniform motion isn’t contained within the idea of a body.

- Contains a priori and a posteriori elements. The ideas of substance and causation provide the necessary framework for the law’s coherence, independent of experience. However, the specific formulation (e.g., “uniform motion”) stems from empirical observation, notably Newton’s experiments. In other words, Kant sees Newton’s laws as synthetic a priori in their “general structure” (e.g., causality), but their “determinate content” (e.g., uniform motion) is empirical. 7

How the synthetic a priori grounds science and metaphysics

As we have seen, metaphysical claims about experience (e.g. “every event has a cause”) and scientific laws are either wholly synthetic a priori or rest on synthetic a priori elements. Kant aims to ground metaphysics and the natural sciences by establishing that synthetic a priori claims are justifiable.

To this end, Kant employs transcendental arguments, or arguments from the mind’s structure. Consider causation:

- To experience the world coherently requires all events to have a cause

- We experience the world coherently

- Thus, all events have a cause

By this, Kant refutes the empiricist who thought metaphysical knowledge was impossible. He secures induction a priori. Concretely, the analytic-synthetic distinction refutes Hume’s argument about induction like so:

- Premise 2: Can we justify it a priori (by pure thinking, without experience)?

No, because we can imagine a world where the sun doesn’t rise tomorrow. It’s not a logical contradiction like saying “1+1=3.” (Principle of Contradiction)Yes, the synthetic a priori claim “similar causes will produce similar effects over time” can be justified by examining the mind’s structures.

Kant also refutes the rationalists by showing that our knowledge is limited to what we can experience. We cannot know things we don’t experience — metaphysical knowledge about God, souls, the beginning of the universe, are all illusions.

Intermission

So far, we have constructed an intuitive grasp of Kant’s system, which offers a synthesis between empiricism and rationalism. We’ve also seen how Kant’s transcendental argument establishes the synthetic a priori as the foundation for science’s universal laws and metaphysics’ core truths. It also sets the limits of human knowledge to what we can experience.

In the next section, we will examine Kant’s system of the mind in detail, and construct a mechanistic understanding of how the passive and active faculties work together to create our coherent experience of the world.

The faculties

Kant thought the mind had two main faculties of processing perceptions: an active and passive faculty.

The passive faculty takes in raw sensory input and organizes it. When you see a chair, it captures the colors, shapes, and textures—brown wood, straight lines, a creaky sound. It arranges these in space, so you perceive a chair “over there,” not a jumbled mess. It also handles inner sensations—like remembering the chair’s wobble or feeling annoyed about it—and orders them in time, so one thought follows another. For Kant, space and time aren’t in the world; they’re how your mind shapes what you sense.

The active faculty, on the other hand, deals with general ideas. It’s what lets you think of a “chair” as a four-legged thing for sitting, or grasp that a kick makes the chair move. These ideas aren’t tied to one specific chair—they’re abstract, applying to any chair or kick you encounter.

Here’s how they interplay to create coherent thoughts:

- Raw perception from the passive faculty: You see green leaves, a brown trunk, and feel rough bark.

- General idea from the active faculty: The abstract concept of a “tree”—a tall plant with leaves and a trunk.

- Coherent thought about something: You recognize, “That’s a tree!”

Or take the chair: the passive faculty gives you brown patches and a creak, shaped in space and time. The active faculty applies the idea of “chair” and “motion,” so you think, “That’s a chair, and it just got kicked!”

To put it in Kantian terms, the passive faculty produces intuitions—sensations (inner or outer) shaped by space and time. The active faculty supplies concepts—general ideas like “tree” or “chair.” When concepts organize intuitions, you get cognitions — intentional mental states, or “coherent thoughts about things”.

Cognitions need both parts. Without intuitions, concepts are ungrounded, like imagining a tree without ever seeing one. Without concepts, intuitions are empty—a blur of green and brown with no meaning. If either is missing, you can’t make sense of anything. Together, they let you navigate the world, from spotting trees to dodging wobbly chairs.

The passive faculty

The passive faculty intuits. Kant uses the term intuition to mean immediate, singular representations of objects. “Immediate” means it comes straight from the passive faculty—no processing by the active faculty required. “Singular” means it’s about one specific thing, not a general idea or rule.

Let’s break it down with examples:

- This apple: When you see a shiny red apple on the table, that’s an intuition. It’s a direct, singular perception of that apple, not apples in general.

- Five apples: Seeing five apples arranged in a bowl is still an intuition. It’s a single, collective impression of those specific apples in space, not a general concept of “fiveness.”

- Feeling tired: That heavy, sluggish sensation after a long day? That’s an intuition too—a direct, singular inner feeling unfolding in time.

- Memory of a song: When you replay a catchy tune in your head, it’s an intuition—a singular mental replay of sounds flowing through your inner sense.

Compare these to a general idea, like “an apple is a red or green fruit.” That’s not an intuition—it’s abstract, covering all apples, not one specific moment of perception.

Furthermore, we can distinguish intuitions by their source:8

- A posteriori intuitions come from experience. Seeing this apple or hearing that chair creak depends on the world hitting your senses.

- A priori intuitions are innate to the mind before any experience. Kant says the mind has exactly two a priori intuitions: space and time.9

Kant argues that space and time are innate to the mind, with a transcendental argument:

- Premise 1: All experience requires intuitions—direct, singular perceptions.

- Premise 2: We can’t have intuitions without space (for outer sense) or time (for inner sense). Try perceiving an apple with no shape or position, or a memory with no sequence—it doesn’t work.

- Premise 3: Since space and time are necessary for any experience, they can’t come from experience—they must be prior to it.

- Conclusion: Space and time are a priori intuitions.

The active faculty

Concepts

While the passive faculty deals with intuitions, the active faculty deals with concepts. Kant uses concepts to mean general ideas.

Again, splitting them by epistemics:

- A posteriori concepts come from experience. For example, “dog” as an abstract concept of a four-legged, barking animal.

- A priori concepts, called the categories (like causation or substance), are innate. We’ll cover these in the next two sections.

The active faculty applies concepts on intuitions to produce cognitions. For example, the intuition of a furry, barking animal, combined with the concept of “dog,” becomes the cognition: “This is a dog.” Also, the intuition of a ball rolling down a hill, combined with the concept of causality, becomes the cognition: “The hill’s slope causes the ball to roll.”

Judgements

Recall that a cognition is the combination of intuitions (outer perceptions or inner thoughts) with concepts (general ideas). There are special kinds of cognitions called judgements10. Judgments are claims you make about the phenomenal world, like “this flower is pink” or “the room feels warm”.

In my opinion, judgements are the most important kinds of cognitions. Everything useful you can say about the world is a judgement — from conveying feelings “I feel sad”, to empirical claims of cause and effect “Drinking coffee in the afternoon disrupts my sleep”, to scientific laws “the motion of a body is governed by the law F=ma”.

We can categorize judgements into two types:

- Judgements of perception are claims of your individual experience. For example, “the room feels warm”.

- Judgements of experience are claims of everybody’s experience — “the room is warm”11 is an assertion that this room is of a certain temperature. These judgements aim for universality, or more precisely, intersubjective validity12 — their truth value depends on whether they apply to everyone.

Making a judgement of perception is simple: your passive faculty supplies the a posteriori intuition of warmth, and the active faculty adds a posteriori concepts like “warm” and “room.

But to make universal claims — judgments that aim to hold true for everyone — you need more than just personal impressions. Kant says you require the grounding of a priori concepts, or what he calls the categories. These categories transform the intuition of warmth into a universal claim. Similarly, they ground all a priori truths we learn about the world, including scientific laws and metaphysical truths.

Categories

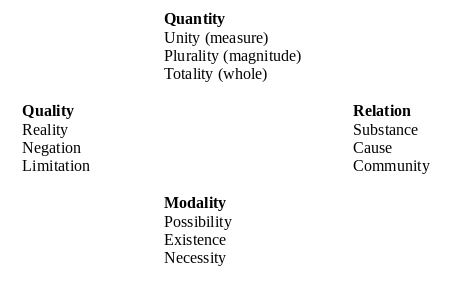

So these are the categories — what Kants posits to be the complete13 set of a priori concepts innate to the mind. They are the logical forms that structure all judgements of experience. Specifically, each judgement of experience takes one moment from each group:

- “The room is warm”:

- Quantity: Unity (a single subject, “the room”)

- Quality: Reality (affirming the room’s warmth)

- Relation: Inherence and Subsistence (warmth as a property of the room)

- Modality: Actuality (the statement reflects a real state)

- “All crows are black”:

- Quantity: Universality (applies to all crows)

- Quality: Reality (affirming blackness)

- Relation: Community (reciprocal relation between crows and blackness)

- Modality: Necessity (a universal, necessary truth)

- “Drinking coffee in the afternoon disrupts my sleep”:

- Quantity: Universality (a general rule about coffee)

- Quality: Affirmative (asserting disruption)

- Relation: Hypothetical (if coffee, then disrupted sleep)

- Modality: Possibility (it may occur under these conditions)

Thus, we come to a full understanding of the active faculty: it applies concepts onto intuitions to produce cognitions. By applying a posteriori concepts to intuitions, it can form judgements of perceptions. By applying both a priori and posteriori concepts to intuitions, it can form judgements of experience. It is these a priori concepts which give judgements of experience their intersubjective validity.

To be clear, these categories cannot be directly experienced. We infer their presence from the logical structure of our judgments. Indeed, upon missing any of the categories, some subset of experience would not be possible.

Moreover, Kant asserts that all rational beings share the same categories, along with the pure intuitions of space and time, enabling a shared, public realm of empirical objects. This universality underpins the possibility of objective scientific knowledge.

The Copernican Revolution in Philosophy

Kant called his approach a “Copernican Revolution” in philosophy. Just as Copernicus realized we should think of Earth revolving around the sun rather than vice versa, Kant proposed that instead of our knowledge conforming to objects, objects (as we experience them) conform to our knowledge.

This paradigm shift resolved the problems that had troubled earlier philosophers:

- Metaphysics: Traditional metaphysics tried to know things beyond experience (God, the soul, the universe’s beginning). Kant showed this is impossible—our faculties only work within experience. Yet unlike the empiricists, he didn’t reject metaphysics entirely. Instead, he transformed it into an investigation of the mind’s structure and the limits of knowledge.

- Science: How can scientific laws be both universal and about the world? Kant showed they’re universal because they reflect the mind’s necessary structures. Science doesn’t discover the ultimate nature of reality but provides systematic knowledge of the phenomenal world.

Kant’s transcendental idealism sparked a philosophical revolution which continues to shape intellectual history. His influence can be traced through major philosophical movements:

-

Marxism: Kant’s transcendental idealism established how mind structures experience. Hegel expanded this idea into absolute idealism, where universal “Spirit” develops through history. Kant’s fixed categories became Hegel’s dynamic dialectical process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Hegel replaced Kant’s unknowable noumenal realm with reality progressively revealing itself. Marx then inverted Hegel’s idealism by placing material economic conditions at the foundation of historical development. He transformed Hegel’s dialectic of ideas into class struggle within economic systems.

-

Political liberalism: Kant’s ethics was informed by his metaphysics. He grounded universal moral principles in rational autonomy. Rawls adapted these concepts into justice as fairness. Their work shapes contemporary liberal political philosophy’s approach to rights, justice, and social structures.

-

Nationalism: Kant introduced the idea of rational autonomy and self-legislation. Fichte reinterpreted this as collective self-determination at the national level. He argued that nations possess unique spiritual characters requiring expression and development. His call for national education systems to cultivate “Germanness” established a model for nation-building through cultural institutions. These ideas spread throughout Europe, inspiring national liberation movements and contributing to modern nationalism

-

Analytic Philosophy: Even philosophers critical of Kant’s system, like Russell and the early Wittgenstein, were forced to engage with his arguments. Contemporary analytic debates about mind, language, and reality often revisit Kantian themes about the limits of knowledge.

-

Phenomenology: Husserl and Heidegger’s investigations into consciousness and being were direct responses to Kantian questions about the conditions of experience. Phenomenology’s focus on how things appear to consciousness rather than how they might exist independently continues Kant’s phenomenal/noumenal distinction.

Transcendental idealism thus stands as one of philosophy’s great watersheds, dividing pre-Kantian from post-Kantian thought. Its insights about the mind’s role in structuring experience fundamentally transformed how we understand the relationship between thought and reality, the limits of knowledge, and the nature of philosophical inquiry itself.

-

The modifier “transcendental” is often used in Kantian philosophy. It refers to the structures of the mind that make experience possible. For example, Transcendental Idealism means experience is conditioned by the mind’s (i.e. ideal) a priori structures; The Transcendental Aesthetic is the claim that space and time exist only in the mind, and structure how things appear to us (i.e. aesthetics); Transcendental Deduction is an argument form that goes something like “if <aspect of the mind> does not exist, experience would not be possible, hence <aspect of the mind> exists prior to experience, that is, a priori” (i.e. deduction); The Transcendental Dialectic is the claim that all cognition that goes beyond possible experience lacks intuitable content, and hence always falls into error — for example, claims about the beginning of the universe (dialectic can refer to overcoming internal contradictions) ↩︎

-

It is illustrative to compare Kant’s metaphysics to Berkeley’s. Kant is an empirical realist and transcedental idealist — things-in-themselves exist “out there”, but what we experience is mind-shaped. In contrast, Berkeley is an empirical idealist and transcendental realist—things exist only as perceptions in a mind, human or divine, but their reality is not shaped by our human minds; it is fixed in God’s mind, independent of us ↩︎

-

This honestly could be mistaken for the drunken ramblings of a tech bro. ↩︎

-

In other words, prior to experience and posterior to experience ↩︎

-

I disagree with Kant’s view that “7+5=12” is synthetic a priori. Mathematicians like Frege argued arithmetic is analytic, with truths derived from logical axioms, making “7+5≠12” a contradiction. Modern mathematics built on ZFC set theory is purely analytic. ↩︎

-

Similarly, I also disagree. In Euclidean geometry, “the shortest distance between two points is a straight line” can be proven by contradiction. Suppose the shortest distance between two points A, B is not a straight line. Find a point C on this line. Then, apply the triangle inequality (which can be deduced from the Euclidean axioms). ↩︎

-

Kant and the Exact Sciences (Friedman 1992) ↩︎

-

Philosophers also call them empirical intuitions and pure intuitions, but let’s stick to one set of terminology for clarity. ↩︎

-

Space is immediate because it is not mediated by concepts. Space is singular because it is a singular whole — there is one space for all all locations. We experience space as the “stage” of all perceptions. Ditto for time. ↩︎

-

An example of a non-judgement cognition is thought “This tree.”. It combines an a posteriori intuition and an a posteriori concept, but makes no claims about the world. For more on judgements, see the SEP on Kant’s Theory of Judgment ↩︎

-

To clarify, “this room feels warm to everyone” is a judgement of perception, as there may be someone who doesn’t perceive the room to be warm ↩︎

-

Kant calls this “objectivity”, which people may find confusing ↩︎

-

A counterexample comes from Hegel: the concept of “becoming”, to understand history or evolution, or “probability” which we have learned is inherent to the structure of the universe due to quantum mechanics. ↩︎